The phrase “to see the light” suggests something hidden will be revealed, which is why light bulbs go off over cartoon characters’ heads when ideas occur to them. But there is seeing the light and then there is truly seeing the light, as the University of Maryland Global Campus (UMGC) exhibit, “Sharon Wolpoff: Wherever I Turn I See Light,” demonstrates.

For the Maryland artist—who paints, makes prints and etchings, takes photographs, makes collages and designs jewelry—light’s emergence creates the conditions for artistic expression. A March 13, 2022, event with the artist turned a spotlight on her latest exhibit at UMGC’s gallery at its headquarters in Adelphi, Md, which runs through June 5.

“For many of us, a ray of sunlight or the light from a light bulb is just something that brightens a space. But Wolpoff views light adorning a landscape or peeping through a window differently,” Eric Key, director of the UMGC arts program, wrote in the exhibition catalog. “She sees more than just a well-lit space; she sees how the space is transformed. She perceives the contrast between dark and light and envisions geometric shapes and angles. She also enjoys exploring how light affects color and creates different shades.”

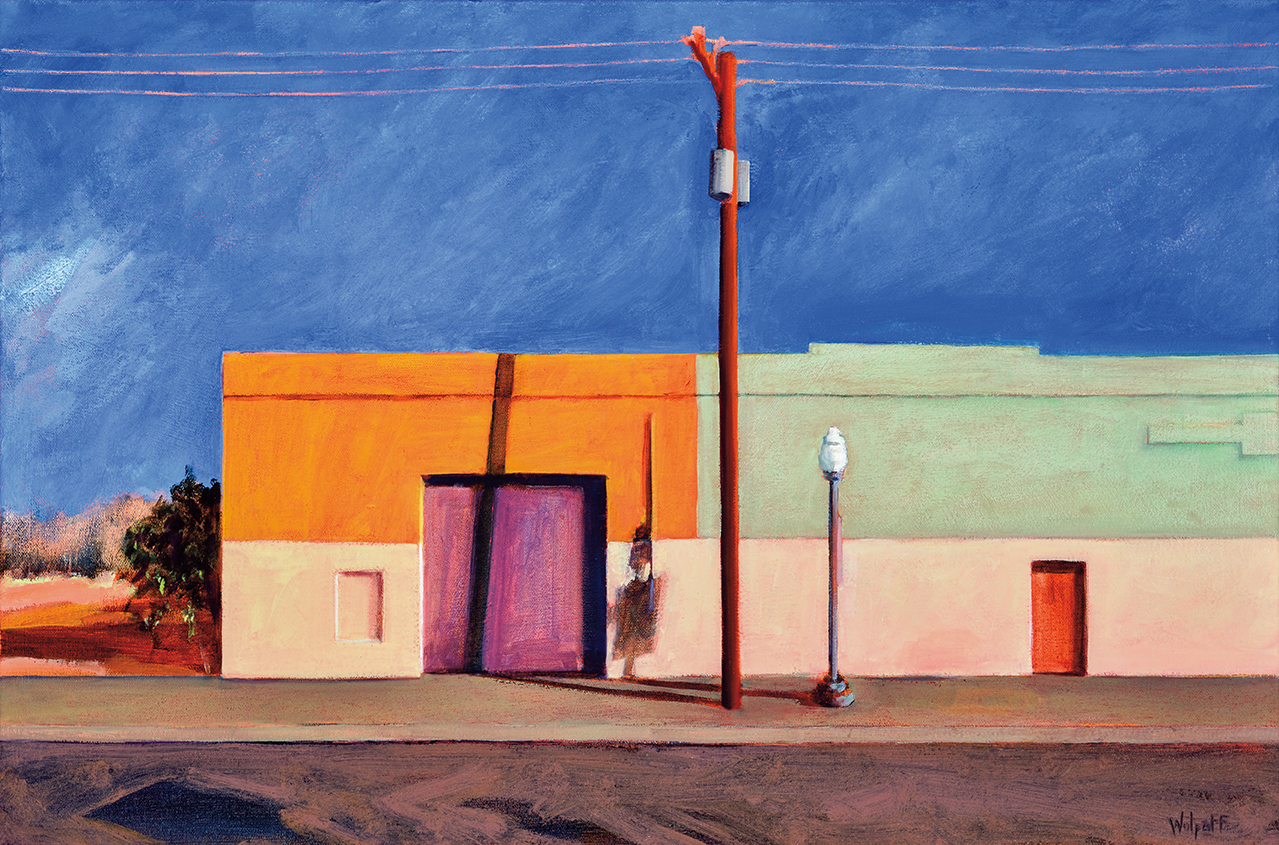

Take Wolpoff’s oil painting “November” (2010), which evokes the urban landscapes of Edward Hopper. An orange-brown telephone pole nearly bisects the canvas horizontally, cutting through both the bright blue sky and the orange, pink, green and off-white and earthy tones below. A smaller streetlight beside the pole echoes its form, and two doors (one pink and one orange) boldly emerge from a nondescript, windowless building on a quiet street.

Most pedestrians might walk by this scene without a second thought. But to the artist, the symphony of light and shadow was irresistible. The diagonal shadows of the pole and streetlight climb up the building, and even though much of the palette is muted, one can tell by the brightness of the lightest colors that this is a sunny day. Just as a Renaissance painting might turn an otherwise typical figure into a saint with the insertion of a halo, Wolpoff has elevated this street scene with its stunning light and shadow.

Whether interior scenes or outdoor landscapes, figures in motion or seated at a table, light is always a protagonist—if not the star of the show—in Wolpoff’s artwork. That is also true in the desert of Tucson, Arizona, one of her favorite locations and a destination she has visited with her mother over the past two decades.

“I would meander through the desert, and this is how the painting got started,” she said of her 2007 work, “Pink Cactus and Agave.”

Wolpoff took many photographs of the sky and the mountains, but two cacti—one pink and one agave (green)—grabbed her attention. She even found them seductive, she told the audience at the UMGC event. Back in the studio, she cut up three photographs she had taken and put them back together as a deconstructed and then reconstructed collage.

She called her technique “structured freedom” because it lets her advance 50 percent of the way before she begins to apply brush to canvas. In effect, she has already mapped out the composition and figured out what is going where. Brush in hand, she then can “relax into the intuitive process of painting,” she said.

“There’s something about the desert, where the perception is that it’s a barren and lifeless place. I found it to be so alive, and it was just a tremendous voracious presence that I wanted to be able to capture,” Wolpoff said.

Here too, of course, her dramatic interplay of light and shadow dances across the landscape.

In an artist statement, Wolpoff called light both part of the composition and a “metaphysical presence.” She explained that the show is called “Wherever I Turn I See Light,” because light “is something we need now more than ever.”

“It’s my intention that this show be offered as a counterpoint to the extraordinary events ongoing in our world today,” she said. “Light is an invitation to encounter the divine spark that exists in all of us.”

When Key first told UMGC President Gregory W. Fowler about the show, the president slipped in to see it.

“I have been inviting everyone I know. It is absolutely stunning,” Fowler said, adding that an arts program at an institution that is primarily online might be a surprise to many people, but not to him.

“There’s nothing more universal, nothing more global than the arts, and the ability for the arts to speak across cultures,” he said.

At the event, he told Wolpoff, “I can’t think of anything that’s more timely than the work that you’ve been doing.” He also said Wolpoff’s “ability to see special things in places where other people may not necessarily is part of what I believe UMGC’s role is: to help those who[m] others might not always see as special, but to find that special light that’s within them as well.”

The president’s experience prior to coming to the university included time at the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The hour-long discussion at the event also featured Julia Langley, faculty director of the arts and humanities program at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, which exhibits Wolpoff’s works, and Myrtis Bedolla, chair of the UMGC art advisory board and owner and founding director of Galerie Myrtis in Baltimore.

The conversation at the event touched on everything from how the artist first became obsessed with light in the late 1970s, when she painted light streaming in a window while she waited for a model who was late, to the fact that she holds a law degree. After failing the bar twice, Wolpoff became a professional artist but, 14 years later, she again sat for the bar and passed.

Wolpoff’s works that were supposed to hang for three months at the cancer center ended up staying for two years. The artist recounted meeting an oncologist at the center, who bought one of her pieces. Wolpoff was introduced to the doctor’s family when she went to the buyer’s home to deliver the work. Two months later, the oncologist called Wolpoff one evening. The doctor had to deliver bad news to a family and wanted first to talk to the artist to lift her spirits. She bought a second painting from Wolpoff during that discussion.

“I was so touched by that. I remember being moved to tears to be part of something like that, and also to get a glimpse of what it’s like,” Wolpoff said. “My perception was, ‘Oh this is for the patients coming in, and then through Julia, I started learning it’s for the staff. It’s for the doctors. It’s for everyone.”

Langley, the program’s faculty director, said it is important to have art in a cancer center—a distressing place where nobody wants to be—to make it more user-friendly and to give people things about which to dream. From the start, Wolpoff’s work drew rave reviews.

“People streamed into my office and said, ‘This is the most amazing show. Please don’t take it down. We love it,’” Langley said.

At the end of the program, when it seemed that all that could be said had been said, Fowler elicited yet another revelation (shedding more light) with a seemingly basic question: Had the artist’s way of seeing light changed over time?

“Yes,” Wolpoff said, noting that she grew increasingly aware of the kinds of auras that surround people. “It has expanded.”

Share This