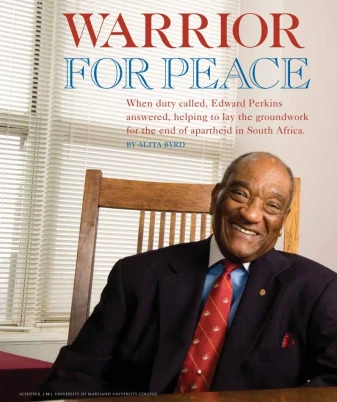

Editor’s Note: As UMGC commemorates African American Heritage Month, we remember one of our most distinguished graduates. This article, written by Alita Byrd, first appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Achiever magazine. Edward J. Perkins—a 1967 graduate of University of Maryland University College (now University of Maryland Global Campus) and the first Black ambassador to apartheid South Africa—died on November 7, 2021, at the age of 92.

In 1986, when President Ronald Reagan named Edward Perkins U.S. ambassador to South Africa, people sat up and took notice. At the time, the South African government was still enforcing a strict system of apartheid, holding African National Congress leaders like Nelson Mandela behind bars, and using repressive laws to keep the majority black population from voting and achieving equality with whites. Perkins—a career diplomat, soldier, and 1967 UMUC graduate—would be the first black ambassador to the troubled country.

Perkins was no stranger to intolerance. He grew up in Louisiana in the 1930s, served in the recently desegregated U.S. military beginning in the early 1950s, and aspired to a career in the overwhelmingly white Foreign Service. And while working in Taiwan, he met and fell in love with Lucy, his wife-to-be—a beautiful girl from a very traditional Chinese family.

“I had the temerity to ask Lucy for a date,” said Perkins, “and she took her reputation in hand to go out with an American.” When Perkins proposed, Lucy’s father locked her in the house and told her brothers to make sure she stayed there. So Perkins sent a driver to rescue her at midnight while he organized a wedding for the next morning, Romeo-and-Juliet style.

“When her family found out she was married, they decided there was nothing they could do,” Perkins said. “Now we are good friends.”

Perkins was equally focused when it came to advancing his career. After first serving in the U.S. Army in Korea and Japan, he remained in Japan while studying Japanese. Always on the lookout for adventure, after returning to university studies in the United States, he and a buddy decided to join the French Foreign Legion, but found they didn’t have enough money to get to France. So Perkins joined the U.S. Marine Corps instead. He recognized the opportunity offered by UMUC’s overseas operations and soon earned his undergraduate degree.

“I think the professors were some of the best I’ve seen,” Perkins said. “Their presentations were challenging and the interest they generated among the students was genuine. One instructor I remember was probably one of the best math and statistics professors in the world. He actually made mathematics come alive.”

Around the same time, Perkins recalled two Foreign Service officers who had made a lasting impression on him when they spoke to his high school class.

“The travel attracted me, and learning languages,” he said. So Perkins took the Foreign Service exam. He didn’t get in, but he was undeterred. The next time, he was accepted and went on to build an impressive diplomatic résumé, serving on the ground in Africa and in policy in Washington, D.C.

He would need every bit of that persistence and experience as he tackled the post in South Africa, where the consequences of failure were grave indeed.

“There was a very tenuous relationship between the U.S. and South Africa back then,” said Perkins. “A growing number of Americans were insisting we should help dismantle apartheid. The president was convinced that if the U.S. did not lend a hand in helping to dismantle this racist government, there could be a race war in South Africa. He decided he had to do something quick and dramatic to show everyone that he did not countenance a government based on race and religion and advantage for one group of people over another. The secretary of state [George Shultz] recommended a black ambassador. He said it was time to send a professional diplomat, so they went down a list of about nine people and finally settled on me.”

Some saw Reagan’s decision to send a black ambassador to a segregated country as a political message to the South African government. But others—including the Reverend Jesse Jackson—criticized Reagan, whom they saw as racist, for doing too little too late. And many, both in the United States and South Africa, saw the appointment as little more than a symbolic step meant to quiet critics who were calling for tougher sanctions against the apartheid government.

Jackson went so far as to ask Perkins to refuse the assignment. But Perkins believed it was his duty as a Foreign Service officer to go, and, in November 1986, he took up his post in Pretoria with Lucy by his side.

“The assignment was to turn the embassy into a change agent,” said Perkins. “I wanted to make sure that everything I did, from the moment I arrived, was focused on bringing about political change in South Africa without violence. That’s what Reagan asked for.”

It was a daunting task. From the first, South African president P. W. Botha—never known for his polished manners—made clear his dislike for Perkins. When Perkins presented his credentials after arriving in South Africa, Botha shook his finger in Perkins’s face and warned him sternly, “I don’t want you getting involved in our affairs.”

But Perkins did get involved—first in Pretoria, then elsewhere around the country, working tirelessly for the duration of his posting. During apartheid, Pretoria was a symbol of white Afrikaaner rule and oppression. The city was hated and feared by black South Africans as a citadel of racist policies. But Perkins was determined not to bow to the rules. He instituted an embassy policy that forbade employees from patronizing establishments that did not accept black customers.

“Pretty soon, all the restaurants around the embassy in Pretoria— which were highly segregated—sent word that they would accept anyone,” Perkins said.

Next, the American embassy organized an exhibition at the art museum in Pretoria, showing the work of both black and white artists and sending invitations to both black and white guests.

“The museum managers were astonished that there were black artists in South Africa,” said Perkins. “[Today], these efforts might not seem all that dramatic, but in a place where segregation was so rigidly enforced, it was a [significant] step.”

Many resented those steps, no matter how small, and Perkins—who spent a great deal of time walking the streets of Pretoria—often was exposed to their open hostility.

“I was hissed at by young Afrikaaner mothers pushing their babies in strollers,” he said. “It was not an enjoyable assignment—it was stressful for all of us—but we had a job to do.”

He began to court the black community assiduously, making contacts around the nation. In Soweto, the sprawling black township outside Johannesburg, Perkins met with civic leaders; in Mamelodi, the largest black township outside of Pretoria, he met with religious leaders. He even met with activists in squatter camps outside Cape Town.

And while he tried to avoid the media spotlight, Perkins didn’t hesitate to make his convictions known.

“I sense a growing realization that a valid political system here must be one that correlates with the demographics of the country—not merely black participation or black cooperation, but a government that truly represents the majority of South Africans,” Perkins wrote in an article published in a South African journal in December 1987. While the United States insisted that this had been its policy all along, Time magazine called the statement “pure dynamite” and a “breakthrough.”

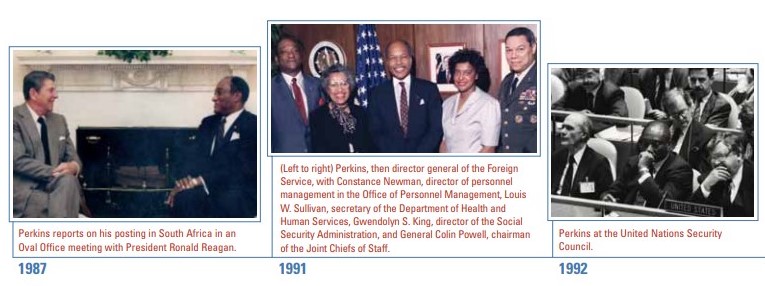

Every couple of months, Perkins flew back to the United States to brief Ronald Reagan on the situation in South Africa. And despite warnings to the contrary, Perkins recalled that he always felt fully supported by the administration.

“Once he made the decision [to appoint me], he never backed off,” Perkins said. “The Afrikaaners tried many ways to go around me to get to him. But Reagan’s response was always, ‘The U.S. ambassador speaks for the American people and this administration.’ Without that complete support, we couldn’t have done what we did. But the president gave me permission to make policy from the embassy in Pretoria—something that never happens.”

Perkins left South Africa before he had the satisfaction of seeing the apartheid government formally dismantled, but there was no question he had helped plant the seeds of change. And although violence occasionally flared as the old government was replaced, the country never spiraled into the civil war that so many feared.

Perkins, meanwhile, went on to serve as Director General of the Foreign Service (the first black officer to ascend to the top position), U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, and ambassador to Australia. Now retired, he remains as busy as ever, serving at the University of Oklahoma as senior vice provost for international programs and executive director of the International Programs Centre, where he holds the Crowe chair in geopolitics.

In 2006, the University of Oklahoma Press published Perkins’s memoirs—aptly titled, Mr. Ambassador: Warrior for Peace.

Share This